I would guess that any reader who has spent a significant period of time studying the life and work of Virginia Woolf must have his or her own "version" of her. In my mind, I have an idea of how she stood, how she walked, the way she moved her head, all culled from photographs and from the many anecdotes and reminiscences I've read about her over the last ten years. There is no film footage of her in motion, and only one surviving recording of her voice, reading an essay called "Craftsmanship" on the BBC in the 1930s: her voice sounds upper-crust, snooty, nineteenth-century, not a bit, in other words, like the fiercely modern voice in her books. While the photographic record is large, it is all those of us who are in love with Woolf (and there is no other phrase which comes close to describing how I feel about her) have in order to create a moving, living portrait in the brain. Thus, each of us must have a personal Woolf, and would probably willingly argue with others about her qualities: "She would never say that!" Or, "She wouldn't wear that kind of dress." This goes a long way towards explaining the problems so many Woolf scholars had with Nicole Kidman's portrayal of Woolf in The Hours--she was simply not their Woolf (nor was she mine, exactly), and so both the performance and the film were dismissed out of hand.

I've seen dozens of interviews with living writers like Doris Lessing and Margaret Atwood, and thus I have some sense of them (however misguided) as people. I can read their books and hear their physical voices in my head; I can see the way they laugh and move. But with Woolf--and indeed with any writer who predates motion pictures--my sense of her exists, for the most part, solely on the page. Perhaps that's where writers should exist most--Lessing certainly thinks so, when she bemoans the interviews and publicity that contemporary publishing demands. The lack of a solid image of Woolf, a voice that can talk in your brain, makes the occasional firsthand account of her all the more valuable. Levenger, the Florida-based company that sells wildly expensive fountain pens, briefcases, stationery, and other "tools for serious readers," recently republished Richard Kennedy's slim 1972 memoir A Boy at the Hogarth Press. As I've been revisiting my dissertation on Woolf's diary in order to expand it into a book, I felt that rereading Kennedy's book was in order, so that I could regain that imaginative grasp of Woolf herself that had begun to elude me in these last months of a very hectic college term.

Kennedy arrived to work at the Hogarth Press, located in the basement of the Woolf's house at 52, Tavistock Square, in 1928, at the age of sixteen, through the auspices of his uncle George, a friend of Leonard Woolf's. At first, he was given odd jobs, but gradually moved up enough in Leonard's esteem (no mean feat!) to begin dealing directly with buyers, "shopping" the books to booksellers in the English hinterlands, etc. A Boy at the Hogarth Press presents itself as a sort of edited diary about his years there, until he leaves after infuriating Leonard by ordering the wrong size of paper for the Uniform Edition of Virginia's novels. In the face of Leonard's wrath, Kennedy quits and enrolls in journalism school, apparently on the sole basis of seeing three attractive young women at University College: "Three pairs of breasts and three laughing faces. They looked so happy and carefree. I thought of that basement prison, and acting on the spur of the moment, I sought out the authorities and learnt that there was a course in journalism starting in the autumn." Despite Kennedy's frequent depictions of Leonard's intolerance and miserliness (he complains about having to shell out money for toilet paper for the office), he maintains that Leonard was in fact a surrogate father for him, and that he learned a great deal in his tenure at the Press.

What is perhaps best about A Boy at the Hogarth Press, at least to my Virginia-obsessed eye, is the light it sheds on Virginia Woolf herself. I've read every biography of Woolf, and am therefore used to having her center-stage. It is always something of a shock to read a biography of one of her relatives or her acquaintances, and see her ambling in from--as Michael Cunningham would put it--her own story. One of things I like most about Frances Spalding's excellent biography of Virginia's sister Vanessa Bell is that Virginia herself is a peripheral figure, and being on the periphery somehow, oddly, makes her come into sharper focus for me. The same is true in Kennedy's memoir. Virginia is glimpsed writing in the back storage room at the Press, setting type, opening packages, and performing other mundane, Press-related activities. During a Bloomsbury evening she is observed in a the corner knitting, "a new occupation for her." One morning she is in a good mood because she spent the previous evening out at a nightclub, and describes "how marvellous it was inventing new foxtrot steps," to Leonard's apparent disapproval. She rolls foul-smelling shag cigarettes that very nearly choke an American lady. Virginia is always "Mrs W" in Kennedy's memoir; she usually calls him "Mr Kennedy." Kennedy appears to have regarded her with a certain degree of awe: by this point she had written Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse, and during Kennedy's tenure there she published Orlando, which was a huge success--Kennedy remarks frequently about their inability to keep the book in stock. We revere Virginia Woolf for her writing, for what she did alone in a room with pen and paper, and naturally many biographies (most notably Julia Briggs' recent Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life) focus on her intellectual and creative life, despite her immersion in the Bloomsbury Group, whose sexcapades have, on the flip side, received an enormous amount of attention. In Kennedy's memoir, it is precisely his record of her attention to the minutiae of the Press that brings her into sharper focus.

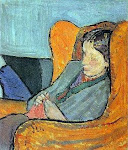

Adding to the appeal of Kennedy's book are his own incredible drawings of Leonard, Virginia, and the other characters who drifted in and out of the Press offices. Virginia never allowed herself to be photographed with her glasses on, and Kennedy's drawings of her, bespectacled, typing and smoking, convey the essence of the woman perhaps better than any photograph. Kennedy became quite well known as an illustrator in later years, and his skill at evoking character and personality through a few mere strokes of pen and ink is stunning. These images, converted in my mind into flesh and blood, add immeasurably to my understanding of how Virginia Woolf simply inhabited a room--an understanding that will undoubtedly help guide my continued work on her diary.

If you're interested in Kennedy's book, you needn't buy Levenger's fancy edition (though it is gorgeous)--Penguin published a mass-market paperback edition, including all of the illustrations, some years back. It is currently out of print, but is available used.

As I get more immersed in my own Woolf project, you can expect more postings on books related to her life and work. I am nothing if not single-minded.

1 comment:

I heard that recording of Woolf sometime last year, possibly while doing an essay on Mrs. Dalloway. I was pretty stunned with how upper-crust she sounded, myself.

Also, having watched The Hour before I finished Mrs. Dalloway (or The Hours as a novel, truth be told [I’m an awful student]), Kidman’s voice has slipped into my subconscious, at least when it came to reading A Room of One’s Own and To the Lighthouse and various other essays. Sorry; I’m new here.

Yes, a hectic semester. We’re all lucky to have survived it. Welcome back to “the blogosphere.”

Paul

Post a Comment